Emerging from Northwick Park Underground station into the 1960s concrete complex which contains St Mark’s Hospital, I am unsure what to find at a world-renowned familial genetics clinic: the Polyposis Registry. I have been invited to look at the registry’s operations by its manager Kay Neale, who was a key contributor to our now-published oral history Witness Seminar on polyposis and familial colorectal cancer. The Hospital’s red-clad entrance somewhat brightens up the grey surroundings, and in the foyer an exhibition of photographs of the Hospital in its former location on City Road in Islington also adds soul to the place: details of the building were nostalgically documented before its move north-westward in 1995, including the former title engraved on its façade which was revised from the Hospital’s first title in 1835: ‘St Mark’s Hospital for Fistula and Other Diseases of the Rectum’.

St Mark’s Hospital, City Road c.1994. Reproduced with permission from Ms Kay Neale on behalf of St Mark’s Hospital.

Kay Neale warmly greets me and my official tour of the Hospital’s heritage begins, past portraits of founding fathers and an intriguing photographic exhibition featuring colonoscopes and the like. The exhibits are a reminder of how specialist this institution is, with knowledge and expertise dating from 1835 to the present.

Historical knowledge is precisely the day-to-day business of the Polyposis Registry, where those with the potential to inherit a polyposis syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), or those already diagnosed with FAP are registered then monitored through regular screening. Referrals to the clinical genetics service, which aims to prevent polyps becoming cancer, are highly dependent on family histories. In the first such enterprise of its kind, the pathologist Dr Cuthbert Dukes began amassing data in 1924 with his seventeen-year-old assistant, Dick Bussey (later Dr Bussey), as Percy Lockhart-Mummery, the senior surgeon at St Mark’s explained in his Lancet paper on ‘Cancer and heredity’ in 1925. He presented compelling evidence from one of his patients, ‘Case 1’, a 31-year-old woman with polyposis:

The patient is one of a family of four, and on her mother’s side had nine uncles and aunts. Seven of these, including her mother, have died of cancer of the bowel at ages between 30 and 54, and her maternal grandfather also died of cancer of the bowel.

Lockhart-Mummery’s account only hints at the motivation required of the clinicians at St Mark’s to gather their patients’ family histories – these efforts became more systematic in the 1950s when prophylactic surgery methods improved. When he wrote this paper, Lockhart-Mummery confirmed that Case 1’s surgery, and follow-up monitoring led to further removal of polyps but these had not yet developed into bowel cancer. Today, similar monitoring of polyps in the bowel or rectum at an early stage of presentation can prevent cancer developing, and is one of the main raisons d’être of the Polyposis Registry.

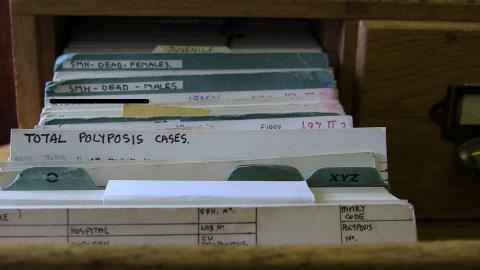

Cabinet with Dr Bussey’s original Polyposis Register patient record cards, St Mark’s Hospital, London.

In essence, the ‘registry’ is the home for the ‘register’; the former being the place and the latter being the patient records themselves (contributors to our seminar tended to use the terms interchangeably). A chain of three cosy offices with well-worn filing cabinets make up the Polyposis Registry where Neale and colleagues guard these highly intimate personal records: medicalized family trees. In Kay Neale’s own office a characterful wooden filing cabinet sits atop a large table awaiting my inspection. She is eager to show me the original cards in the cabinet’s bijou drawers that populated the register, when it was a manual system. Neale worked directly with Bussey in the 1970s and she recalls him leafing expertly through the cabinet, preferring it to the computer system that supplanted the paper cards.

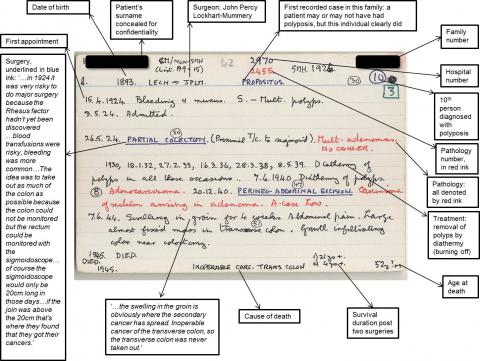

As the image of the card reproduced below shows, they are incredibly neat, colour-coded index cards packed with snippets of an individual’s life story, at least the parts that relate to FAP. No doubt like many such medical records, they feel personal and impersonal in almost equal measures. During my interview with Kay Neale, recorded in the appendix of our publication, she reveals something about the cards that might easily confuse historians. Though these are indeed the ‘original’ patient record cards, they were not produced in the mid-1920s when the earliest cases of polyposis were logged at St Mark’s by Dukes and Bussey. Data records of that period were transposed by Bussey, Neale thinks either in the 1950s or 1960s, but the date cannot be certain, as he worked towards his PhD (awarded in 1970). This discovery in conversation with Neale reminds me of how critical oral history is for providing new clues about archival evidence that may slip through the net and lead to misinterpretation. How readily one might jump to the wrong conclusion without the benefit of the face-to-face testimony of Neale; her dedication, and her depth of knowledge. How easily history can be misinterpreted and yet, despite the provenance of the St Mark’s patient record cards, the data itself is authentic and does originate from the first consultations with the individuals they represent.

Sample of a Polyposis Registry patient record, annotated in consultation with Ms Kay Neale, St Mark’s Hospital, London.

(Download an image of the card:  01 St Mark's patient card 1893.jpg)

01 St Mark's patient card 1893.jpg)

In 1991, DNA samples from patients who were logged on St Mark’s Hospital polyposis register were critical to the identification of APC, the polyposis gene. Without the system Dukes and Bussey set in motion in 1924, and that inspired other registers to be created internationally, it might have taken a lot longer to provide a genetic test for this condition. Despite the compelling evidence that St Mark’s amassed about what is now the institutionalized field of clinical cancer genetics, historically these researchers were somewhat out on a limb. Other contributors to the Witness Seminar explained how family cancer clinics, more generally, only really got going in the 1980s to 1990s, underscoring just how pioneering the work at St Mark’s has been.

The story of St Mark’s Polyposis Register is one reason why this was such a fascinating volume to edit with Professor Tilli Tansey. Insights into research on other cancers from the Witness Seminar’s participants, such as hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) are equally intriguing; revealing, for example, the importance of Professor Jane Green’s road trips in Newfoundland to track down family connections.

You can freely download the volume at http://www.histmodbiomed.org/witsem/vol46

For the Polyposis Registry, see http://www.stmarkshospital.org.uk/the-st-marks-hospital-polyposis-registry

The records of St Mark’s Hospital 1840–1996 are deposited at St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archives and Museum, reference 405 K, see http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/19290961-fc1f-43a3-bdec-cfc5569fe055

An earlier blog piece for the Family History of Bowel Cancer Clinic, West Middlesex University Hospital is available here: https://familyhistorybowelcancer.wordpress.com/2013/11/04/guest-blog-wellcome-witnesses-to-contemporary-medicine-series-clinical-cancer-genetics-polyposis-and-familial-colorectal-cancer-c-1975-c-2010/

See also Granshaw L. (1985) St Mark’s Hospital: A social history of a specialist hospital. London: King Edward’s Hospital Fund.