The 29th February is known to be the traditional day on which women are allowed to propose to men; it is also the day on which many people finally celebrate a delayed, and apparently youthful, birthday. A friend of mine today celebrates his 24th birthday, although chronologically he is in his mid-90s.

Someone who chooses the leap year day for an important event, such as a wedding or an announcement, is quite deliberately selecting a notable date; she or he is making a specific statement that here is something special or extraordinary. Sir Henry Wellcome was such a person, who, newly knighted in the 1932 New Year’s Honours List, signed his Last Will and Testament on 29th February of that year. In it, after a few personal bequests, Wellcome left all his assets, which comprised his pharmaceutical company and all its international branches, library and museum collections, and several separate research laboratories, to five named Trustees. His instructions were to support work in medical research and history of medicine.

A printed copy of Henry Wellcome’s Will, dated 29th February 1932, which established the Wellcome Trust (detail). Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

After Wellcome’s death in July 1936, and the resolution of several legal and financial problems, the Wellcome Trust began, in a rather small way, to support the research activities and areas that he had specified. Now, after several further developments, diversifications and investments, the Wellcome Trust is one of the world’s largest medical research charities (see http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/History/WTX052938.htm and http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/Investments/History-and-objectives/index.htm for further details).

Henry Wellcome was an amazingly successful and innovative pharmaceutical entrepreneur. In particular, he had a flair for publicity, and coined the word ‘Tabloid’ for example, as the brand name for a range of his products – now a word in frequent, if often derogatory, use.

A Tabloid product, Forced March, produced by Burroughs, Wellcome & Co. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

However, from 1884 until his death, the word ‘Tabloid’ was vigorously defended as a trade name of the Burroughs Wellcome company. Indeed, in 1904, there was a sensational ‘Tabloid Case’ at the High Court in London in which Wellcome was supported by more than 70 medical men, including some of the most eminent practitioners in the country, who argued that the word denoted the high quality products of his company, and only his company. He won the case.

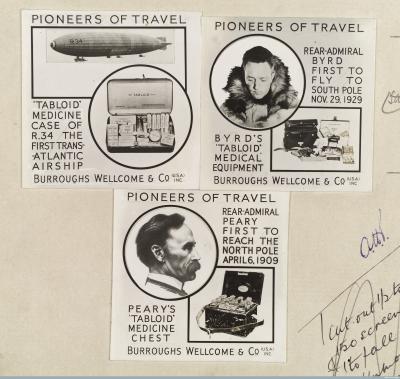

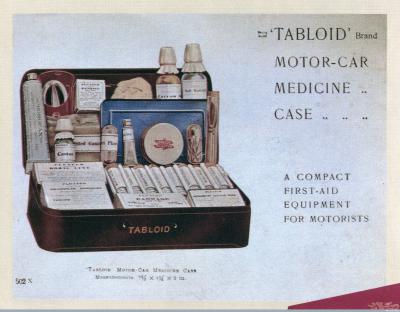

It was Wellcome too who personally promoted the company’s support of high profile expeditions by providing medicine chests for explorers venturing into remote parts of Africa, up mountains, across deserts and to both Poles. He also encouraged the creation of smaller domestic medicine cases which were designed for use on new forms of travel; for use on airplanes, in motor cars, and even for bicycles.

Publicity material for Burroughs, Wellcome & Co medicine cases, from a Company scrapbook. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

A Tabloid motor-car medicine case, c.1920. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

The company’s unicorn logo, adopted in 1908, also came under Wellcome’s personal scrutiny. The legendary horn of the unicorn was reputed to possess medicinal properties, especially as an universal antidote to poison, which is probably why Wellcome chose it as a symbol for his pharmaceutical firm. He gave clear instructions to his designer, Mr Scobie of the College of Heralds, that he wanted ‘delicacy and refinement, and grace with virility and verve’. Earlier drafts were rejected because ‘… the horn is not quite as perfect as it was. The shaping of the upper part of the right hind leg is not quite satisfactory and the hooves require very slight modifications; the chest is a little exaggerated’ (McDonald, 1980).

The unicorn logo of Burroughs Wellcome and Co. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London.

A man with such keen attention to detail, and an eye for publicity and promotion, was not likely to make a mistake in dating his Will, especially such an unusual Will, and one that he hoped would have far-reaching consequences for medical and historical research.

Further Reading

Church R A, Tansey E M. (2007) Burroughs, Wellcome & Co. Knowledge, Trust, Profit and the transformation of the British pharmaceutical industry, 1880–1940. Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster.

McDonald G. (1980) One Hundred Years: Wellcome in Pursuit of excellence. The Wellcome Foundation, London.

Tansey E M. (2008) Vendre medicaments arreu del món: L’empresa farmacéutica Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Mètode: (Science, publicity and propaganda) 59: 85–91.